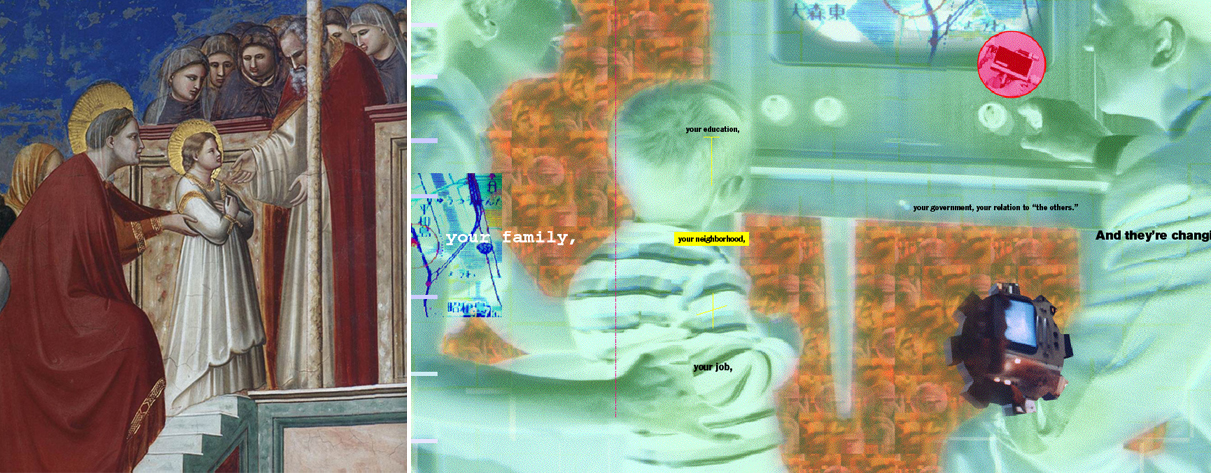

The Medium (after The medium is…, 1993)

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art Digital Witness exhibition examines the impact of digital manipulation tools from the 1980s to the present, for the first time assessing simultaneous developments and debates in the fields of photography, graphic design, and visual effects.

From digital witness to AI captive?

The first Wired visual essay for the launch of magazine in 1993, by M-A-D

The past 40 years saw three technological revolutions: the personal computer, the internet, and the smartphone. Through these phases design became increasingly technological in nature without bringing significant insight. From a social-science perspective early forecasts such as Marshall McLuhan’s 1967 observation that “The medium, of our time is reshaping […] is reshaping every aspect of our personal life.”

As predicted, key aspects of human life have undergone profound changes, so vast and complex that they often defy comprehension. Even those who initially appeared to dominate these new realms like AOL and Intel have lost their hold. Now this chain reaction may well be beyond our control.

The first M-A-D visual essay for the launch of Wired magazine in 1993 was in part inspired by Giotto’s The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, 1305

Three generations ago, our screens appeared as blinding windows of limitless powers allowing us to turn the real into electronic representations. One could see this digital radiance as revolutionary, or even mystical, as expressed in our first Wired visual essay inspired by Giotto. Today a long emerging medium with seemingly divine powers is here able to read our minds, fake our voices and turn the simulacrum into our lived-in reality.

Before investigating the potential of these new tools at the fingertips of our minds we may want to look into our rearview mirrors. Humanity is naturally drawn to the pursuit of truth and enlightenment. With curious minds we find it inward and outward in our daily lives and in the realms of science philosophy and so many exploratory domains. Knowledge is in every aspect of reality if we know to seek proper interpretations. Yet, we are more attracted to narratives that simplify existence and soothe existential discomforts. The raw material of knowledge can feel elusive, leading many to embrace commodified illusions—packaged as enlightenment—that flourish on screens but rarely resonate deeply within our consciousness.

Progress versus profits? Technological innovations may well be the main driver of how knowledge can be manifested through free dissemination, or through control. Their implications are often too complex to be grasped. They are over hyped, often misunderstood and yet blindly adopted. Design is always first to be complicit in how truth finds its way into our minds. It is at the intersection of real world conditions, and the alienation of always-on surveillance capitalism along with the gimmicks it thrives on. Commodified innovation, like gravity, is inescapable. Artificial intelligence (AI), with its ability to generate hallucinations, challenges us to either accept these constructs as enriched reality, or to see them as mere artifacts of the machinic era we inhabit until we conceive a new idea of what we can and must become. This may be the greatest tasks of design.

Design, at its core, seeks to engage the mutations of our times. It translates functions into objects symbolic or physical with a destiny to be distributed, used, and discarded. Historically, design has grappled with the concrete challenges of representation and interface, but now as these functions are increasingly resolved through automation one may wonder how much control we still have over the objects that are being conceived. We face an ontological shift where infinite possibilities come with challenges too complex to be fully understood. In the meantime we move along half blind and trying to interpret the implications of generative creation.

Creation versus production? For millennia, the nature of creation has remained fundamentally unchanged even with inventions like the printing press and photography. The nature of man-made form is what oversaw radical transformations, as it is informed less by subjects and more by its materialities—be it minerals, synthetic compounds, or artificial matter. A portrait is a portrait, but there is a vast difference between one made of marble and a photograph, and even more with unpredictable generative imagery whose materiality may be user “likes”, algorithms and large databases. AI is meant to please and not to be critical of itself. It only knows learning and iterative production filtered through user engagement. That is why it often generates lavish expressions rooted in art nouveau more than in modernism. In turn, we are influenced by AI, as we are by the output of social media creations.

In all visual design disciplines from illustration to architecture, we have learned to find our references on screen more that in the physical world. After learning to control forms with software, keyboards and tablets we now are shifting toward prompt writing. Since language is the new interface between our imagination and what can be generated, now is a time when we may see a radical shift in the nature of creation. To start with, words and forms are different domains not always in synch, and AI’s misinterpretations bring further value to this sort of co-creation. Such glitches can loosen our control over the process and reveal our own creative limitations. In the meantime, the machine increases its ability to control the process and ideally we can learn from each other.

The design praxis directly reflects the transformations of technology. What was once firmly under human control—shaped by our hands, eyes, and tools—has been increasingly delegated to machines during the past five centuries. Not only is form now being produced automatically, but a new kind of machine-generated imagination is emerging. We are facing choices between resisting these new tools and risking the inability to operate in this modern world, or embracing co-creation with technology and the risk of losing our capacity to imagine. Whether we engage or disengage, this gap between human and machine, is what may reveal our long conflictual relationship with technology.

Artificial intelligence should not be seen as just another novelty but rather as a culmination of technological evolution. Technology is no longer a tool or medium—it has become our canvas and atmosphere and perhaps a part of our consciousness as we slowly become part of its consciousness. Generative AI highlights how deeply entwined we are with technology as it grew from physical tasks to conceptual ones. It always moves faster than we can fully comprehend, presenting novel opportunities and thrills we celebrate as progress and enchantment—only for us to later grapple with the negative externalities and the controls we’ve ceded.

Intelligence versus intelligence? As early as 1956, the Dartmouth workshop proposed that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.” Today, the pressing question is whether humanity can summon its own wisdom to always question the output of the machines that we have created and are now becoming increasingly autonomous. From this quest we can learn if humans are so intelligent in the first place. We may speculate that our current design challenge is to worry less about its forms and more about its functions in serving the web of planetary needs from organic life to humans to be born, and the technologies in-between.

[»other Wired intros by Erik Adigard, M-A-D]

IN: print