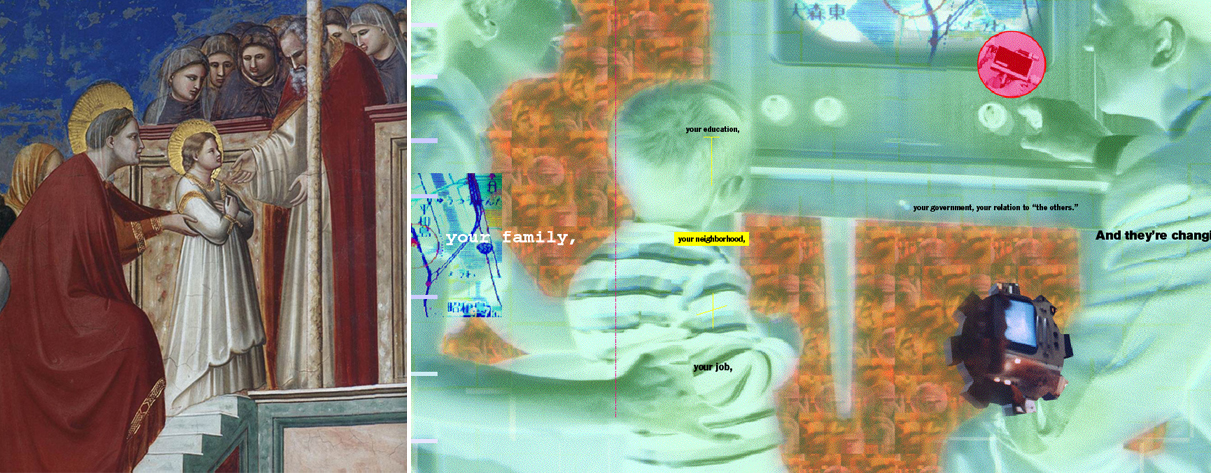

The Medium (after The medium is…, 1993)

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art Digital Witness exhibition 24Nov24-13Jul25 examines the impact of digital mediums from the 1980s to the present, in the fields of photography, graphic design, and visual effects.

From digital witness to AI captive?

The first M-A-D visual essay for the launch of Wired magazine in 1993

The past 40 years saw three technological revolutions: the personal computer, the internet, and the smartphone. During which time design continued to adapt to new tools and shifting market demands. From a social-science perspective early forecasts such as Marshall McLuhan’s 1967 observation that “The medium, of our time is reshaping […] every aspect of our personal life.” have remained true in ways that often defy comprehension.

Three generations ago, our screens appeared as blinding windows of limitless powers allowing us to turn the real into electronic representations. One could see this digital radiance as revolutionary, or even mystical, as expressed in our first Wired visual essay inspired by Giotto. Today a long emerging medium with seemingly divine powers is here able to read our minds, fake our voices and turn the simulacrum into our lived-in reality.

Before investigating the potential of these new tools at the fingertips of our minds we may want to consider how humanity is naturally drawn to the pursuit of enlightenment. We find it inward and outward in our daily lives and in the realms of science, philosophy and other exploratory domains. Knowledge is in every aspect of reality if we own the keys of interpretation. The raw material of knowledge can feel elusive, so we can easily be attracted to the comfort of narratives and illusions offered to us as packaged enlightenment to simplify existence and sooth existential discomforts.

The first M-A-D visual essay for the launch of Wired magazine in 1993 was in part inspired by Giotto’s The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, 1305

Progress versus profits? Technological innovations, through customized dissemination are the main drivers of how specific notions of knowledge can become manifest. Their implications are often too complex to be observed. They are over hyped, often misunderstood and yet blindly adopted. Design is always first to be complicit in how truth finds its way into our minds. It is at the intersection of real world conditions, and the alienation of always-on surveillance capitalism along with the gimmicks it thrives on. Commodified innovation, like curiosity, is inescapable.

Design, at its core, seeks to engage the mutations of our times. It translates functions into objects whether symbolic or physical with a destiny to be distributed, used, discarded and then renewed. Design has always grappled with the concrete challenges of representation and interface, but now these functions are increasingly resolved through automation and backend processes. One may wonder how much control we still have over the objects that we conceive. We face an ontological shift where infinite possibilities come with challenges too complex to be fully grasped. In the meantime we move along at full speed, half blind and trying to interpret the implications of generative creation.

A 2024 concept design inspired by M-A-D’s first Wired visual essay for the launch of the magazine in 1993.

Creation versus production? For millennia, the nature of creation has remained fundamentally unchanged even with inventions like the printing press and photography. However, the nature of the forms we produced is what oversaw radical transformations. Forms are informed less by subjects and more by materialities—be it minerals, synthetic compounds, or artificial and immaterial matter. A portrait is a portrait, but there is a vast difference between one made of marble and a photograph, and even more between the latter and a generative image rooted in algorithms and large databases. It only knows learning and iterative production filtered through user engagement. That is why it often generates lavish expressions more than visual restraint. Ultimately, we are influenced by AI trends, as we have been by the past decades social media creations.

The design praxis directly reflects the transformations of technology. In all visual design disciplines, we have learned to find our references on screen more than in the physical world. What was once firmly under human control—shaped by our hands, eyes, and tools—has been increasingly delegated to machines. After learning to control forms with software, keyboards and tablets that we owned, we now are shifting toward on-demand prompt writing. With language as a new interface between our imagination and what can be generated, we may see a radical shift in the nature of creation. The mix of words and AI processes is our new materiality. To start with, words and forms are different domains not always relatable. AI’s misinterpretations often bring unsuspected value to this sort of co-creation. Such glitches can loosen our control over the process and reveal our own creative limitations. In the meantime, the machine increases its ability to control the process and further challenge our ability to freely imagine.

Not only is form now being produced automatically, but a new kind of machine-generated imagination is emerging. We are facing choices between avoiding these new tools and risking our place in the modern world, or embracing co-creation with AI and the risk of weakening our imagination. Whether we engage or disengage, this gap between human and machine, is what may reveal our long conflictual relationship with technology.

Generative AI highlights how deeply entwined we are with technology as it grew from physical tasks to conceptual ones. It always moves faster than we can adapt, presenting novel opportunities we celebrate as enchantment—only to later grapple with the negative externalities. Artificial intelligence should not be seen as just another novelty but rather as a culmination of an evolution where technology has become our environment and perhaps a new kind of shared consciousness.

Intelligence versus intelligence? As early as 1956, the Dartmouth workshop proposed that “every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.” Today, the pressing question is whether humanity can summon its own wisdom to always question the output of the machines as well as its relentless growth. From this quest we can evaluate our own intelligence in the first place, and our skills to address the web of planetary needs from organic life to the humans to be born, and the technologies in-between.

Erik Adigard, M-A-D