Erik Adigard interviewed by Nikolai Vogel

Erik Adigard interviewed by Nikolai Vogel / 14.06.2019

Nikolai Vogel: What‘s so special about Bauhaus? What do like?

Erik Adigard: As a designer I was brought up with the canons of Bauhaus. And thencoming out of the 80s and the 90s and the emergence of technology in the San Francisco Bay Area where I was very active early on, I always thought that the Bay Area had inherited the spirit of the Bauhaus. When I was working at WIRED we wanted to start a new school, which would be a new Bauhaus, a digital Bauhaus. We thought that we needed to get out of the chaos of industry and commerce in order to free digital design through new principles, that we were going to reclaim the ownership of the tools and technology to redistribute it to the creators. In the 80s when I arrived in the Bay Area there was still the revolutionary spirit of the 60s and 70s, an appetite for creative minds who have Utopian ideals and can come up with new political and social strategies to free and enlighten the world.

Another interesting thing in this sort of rethinking was how we learned and inherited from the Bauhaus, and the fact that on the West Coast we also inherited a great deal from eastern philosophies and interpretations of history that were challenging us to rethink form, the nature of form and also the needs that were out there, needs that weren’t always connected to industry and commerce. For me, there are three Bauhaus participants who are most interesting. They are Itten, Moholy-Nagy and Schlemmer. They are the three visionaries. In their own unique ways, they challenged the nature of creation. On one end, spirituality, on the other end, the machine. This tension, where they all basically are trying to hold on to a certain interpretation of spirituality and at the same time they are all – even Itten –relating their praxis to design and technology, but not just mechanical technology, also conceptual technology. Itten was not so much working with machine as he was working with design systems. All three were working with new design systems of their own. Obviously in the Bay Area we had these new tools that were very quickly becoming more and more complex, we had digital tools that were quickly becoming more and more complex, we had digital tools that evolved into digital media and digital media very quickly opened up into digital environments and into social environments, where the creator basically began to understand that, “okay yesterday I was doing singular forms and now I’m beginning to enter investigative territories where one has to constantly remap the territory.” I think remapping has become a continuously unfolding challenge in this dawning age.

In the way we are working we have mechanized the languages that we have inherited, like the long tradition of text making. In a way text is dead and the word has taken over. And I would say that image is dead and the icon has taken over. We could actually take it a step further and wonder if the sensation has taken over everything.

NV: And what do you think is now special about SENSEFACTORY?

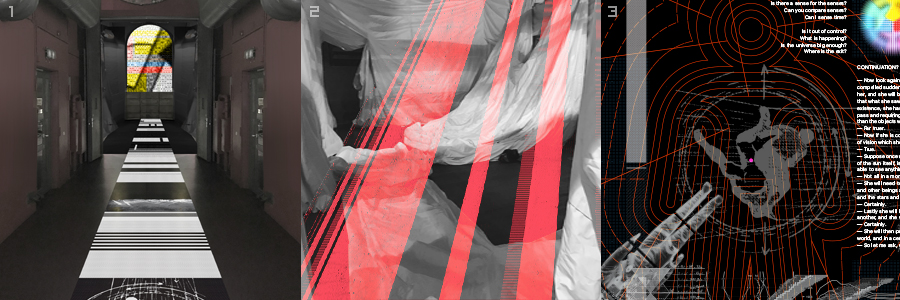

EA: The people! For me the extraordinary opportunity is the attempt to bring to life the concept of the “Mechanized Eccentric” where multiple disciplines, media, techniques, creators and minds can come together to create something that is going to be, through its very chaotic making, able to figure out the relationship between logic, poetics and aesthetics and somehow through the process is going to help us reveal new questions, and that is actually going to be an exploration. It’s a research for me. I think the outcome are discoveries and elements of discovery. The outcome are questions. This project is inherently unstable, unpredictable, and nearly miscalculated by design. This is a project of entropy, it is full of contradictions. At the same time, it is a constant unfolding, and a long immanence. It’s like a long play in three acts. As you’re being brought into this place that is the Muffathalle,it first opens into a cathedral reference and then you unknowingly enter a monumental thing that refers to many things all at once. You are entrapped in it. That thing that is actually its own organism, its own metabolism, its own body, is entrapping you and is beginning to raise questions on the difference that there is between you and the machine, or you and your body and mind. You don’t know what it is, you can’t really make sense of it. There is a point where you may lose your own anchors or you may perceive what might be the climax of the dramaturgy. To me, among others it brings up the image of the Raft of the Medusa, because it floats as well as because it is only an art work and not the real thing. The raft is all about surviving some sort of massive shift, not just a storm.

When you emerge in the third part you are at last invited to enter a phase of questioning the interpretation of it all – looping back to where you came from, and at the same time, where are you going. It is the confrontation of a question that transitions like a cold shower from intense sensation to intense intellectual confrontation. In my mind the notion of transition is what the dramaturgy is about.

NV: So you take this as a metaphor for perception?

EA: Well, in that metaphor, the ones who do not survive are the ones who do not land in a space of interpretation, of dénouement and resolution. If we only settle for superficial sensations, in my mind we will return to a shallow preformatted life of and therefore will die without having really sensed and understood whatever happened to us in this world. That’s the reason why I’m interested in what we’re doing, because I’m realizing that I’m actually caught in that lack of experience myself, all the while drowning into a constant stream of commodified sensations all claiming to help me make sense of life.

NV: So, we’re addicts to our senses in a way?

EA: I think we are not even aware of the senses. I think what is crazy is that the problem is in the relationship we have with the sensors not the relationship with our senses. All senses are being neutralized in this relationship. There is no collateral damage assessment. I think that collateral damage assessment is super important. In a way this project is one way to look at that issue. It’s there to ask you: Did you ever wonder about the damage that is going on with your relationship with the sensors that you have purchased and that you have voluntarily adopted in your everyday life? Nobody really forced you. Are you aware of this relationship between you and the sensors? Maybe not. I would like people to emerge from SenseFACTORY and say, “Okay I have never thought about that myself. Gee! I just wanted a new iPhone because my old iPhone didn’t work anymore. But suddenly this iPhone now is way more loaded with sensors. And it already is an old iPhone!”

NV: So you describe the project also as a kind of passage for the visitor?

EA: Oh yeah! I think that this project is an opportunity. It’s a journey, that’s why I like the raft metaphor. Of course, it’s inflatable, so it floats through a space of infinite realities. This structure is a living body and it carries you. It is a vessel to go through a storm. We could say it’s like a sensual storm. I think that this raft is carrying us as long as we can go through this journey, as long as it takes us to understand – whether it’s a cathedral, a raft, a cave or whatever, it’s an escape. When you enter, you already enter into an exit. This entire experience is about the exit. The exit is what we are trying to invent here.