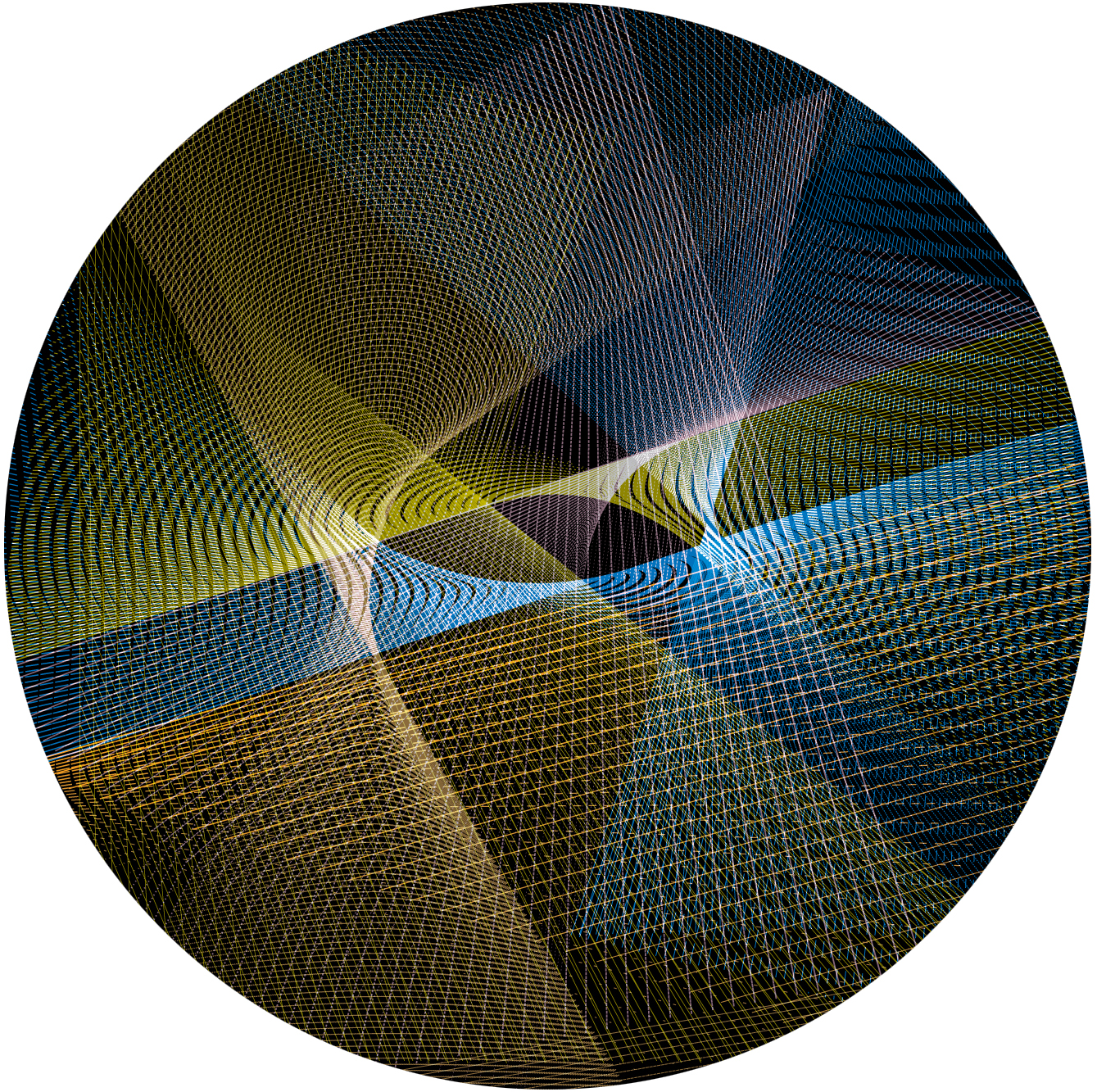

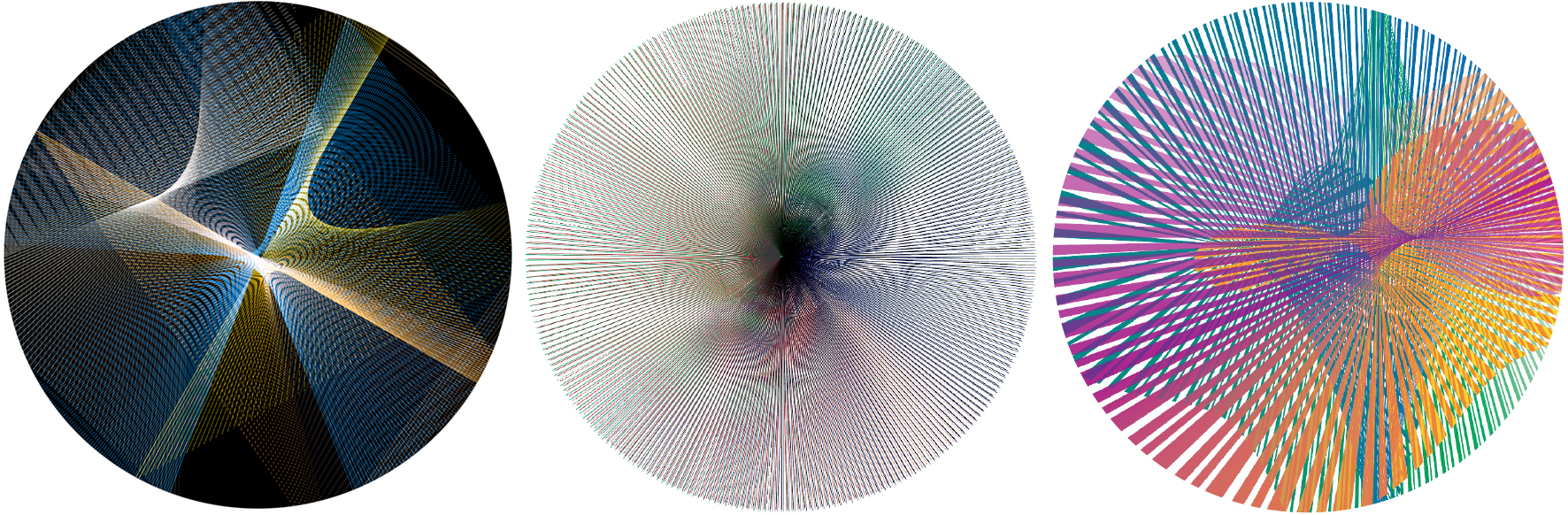

Colliderosope series

Colliderosopes conceived for David Howes’s latest book The Sensory Studies Manifesto: Tracking the Sensorial Revolution in the Arts and Human Sciences, published by University Of Toronto Press

*a Marshall Mcluhan notion

David Howes, Concordia University: The designs are intended to express the holism of the concept of the sensorium, as well as its dynamism. In “The Shifting Sensorium” (1991), Walter J. Ong defined the sensorium as “the entire sensory apparatus as an operational complex.” Ong further proposed that “differences in cultures … can be thought of as differences in the sensorium, the organization of which is in part determined by culture while at the same time it makes culture” (Ong 1991: 28).

Ong was a student of the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, author of The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962). McLuhan regarded media of communication as “extensions of the senses.” One of his favourite tropes for the sensorium was the kaleidoscope. With each twist of its shaft, the kaleidoscope reveals a different alignment of shapes and colors just as, with the introduction of each new technology of communication (e.g., writing, print, electronic media) the divisions and relations among the senses are altered, giving rise to new “sense ratios.” McLuhan also used the term “collideroscope” (which he borrowed from James Joyce) to highlight the tensions as well as the synergies of the sensorium as an operational complex.

Another image that I proffered in the course of our discussion was that of the fugue. This suggestion was inspired by the section on the “Fugue of the Five Senses” in the first volume of Lévi-Strauss’ Introduction to a Science of Mythology: The Raw and the Cooked (1983). When I read Lévi-Strauss on the sensory codes of Amerindian mythology, I am reminded of J.S. Bach’s Goldberg Variations, particularly as interpreted by the great Canadian pianist, Glenn Gould, first in 1955 and then again towards the end of his life, in 1981. As Edward Said observes in “The Music Itself: Glenn Gould’s Contrapuntal Vision” (1983), the essence of a fugue consists in the simultaneity of voices: a melody is always in the process of being repeated by one or another voice … Any series of notes is thus capable of an infinite set of transformations, as the series (or melody or subject) is taken up first by one voice then by another, the voices always continuing to sound against, as well as with, all the others (Said 1983: 47).

The sound-image of the fugue appealed to me for the way it evokes the concept of intersensoriality, which was also central to the Manifesto. This term refers to “how the relations between the senses, and the correspondence or conflicts between their deliverances (colours, sounds, perfumes, etc.), are constituted differently in different societies and epochs” (Howes 2022: 69-70).

Following our phone call, Adigard went away and came back (in very quick order, because he had already been experimenting with McLuhan’s notions in his other work) with not one but a whole series of designs – or medallions, as I think of them – to express this idea of the endless variations to the interrelations of the senses. He calls them “Collideroscopes,” in homage to McLuhan.

What a wondrous way of visualizing the sensorium Adigard’s medallions present! Looking at the designs, with their endless series of variations on and transformations of the lines and shapes – of music as of sight – you can virtually see the fugue and hear the kaleidoscope.

Adigard’s illustrations are in line with the medieval notion of the “Wheel of the Senses,” as in the wall painting at Longthorpe Tower, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, UK, ca. 1320–1340 (also featured in this Picture Gallery) and resonate just as forcefully with the transfiguration of the senses in the contemporary period: the “Age of the Digital Baroque” as Richard Sherwin (2011) dubs it, such as the eyeborg, sensory substitution systems, “sensing machines” (Salter 2022) and other such virtual augmentations of the human sensorium.

Now that my search for a cover illustration for the Manifesto has been sorted, the next step will be to transpose Adigard’s medallions into tastes and smells and textures. To perfume them, I plan to ask Caro Verbeek: for her doctoral research, Verbeek (2020) set herself the task of recreating the perfumes of the Futurist art movement. To taste them I will seek the guidance of the experimental psychologist Charles Spence, co-author of The Perfect Meal (Piqueras-Fiszman and Spence 2014) and his frequent collaborator, Chef Jozef Youssef of Kitchen Theory. To feel them, I think David Parisi, author of Archaeologies of Touch: Interfaces of Haptics from Electricity to Computing (2018) may have some suggestions.

And while we are at it, we must not overlook the interoceptive senses (proprioception, kinesthesia, etc.) as disclosed by Mark Paterson in How We Became Sensorimotor (2021) nor the spiritual senses as anatomized by the theologian Origen. “According to Origen these senses enabled one to perceive transcendental phenomena, such as the sweetness of the word of God” (Classen 1993: 3); so too could this doctrine explain the phenomenon of the blessed “hearing voices” or having a “vision.” When you think about it, the varieties of sensory experience are endless, or “passing strange and wonderful” in the words of the poet quoted by the great human geographer Yi-Fu Tuan (1993) in the title of his book on aesthetics, nature and culture. We really must discard the idea, bequeathed to us by John Locke in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) of the senses as passive receptors of the impressions of the external word. The senses are inter-active, both with the world and one another!

IN: print